The Mexican American population grew because of both migration and the growth of families. Barrios or neighborhoods developed. Among them were El Huarache (the sandal), located along Mosley with El Rock Island to the north, and La Topeka, to the west on Topeka Avenue. These were modest areas among the railroad tracks, grain elevators, stock yards, and foul-smelling packing plants. However, it also offered opportunity. These communities often kept to themselves and formed institutions to support one another from mutualidades (mutual aid societies) to sports clubs. Religious institutions, such as Our Lady of Perpetual Help and the Mexican Baptist Church were community hubs.

This painting, called "The Junction" dates from 1932 and is the work of local artist Edmund L. Davison. It shows the grain elevators and railroad tracks of north Wichita. Nearby would have been the barrios of Latino families. Courtesy Edmund L. and Faye Davison Collection, Wichita Art Museum

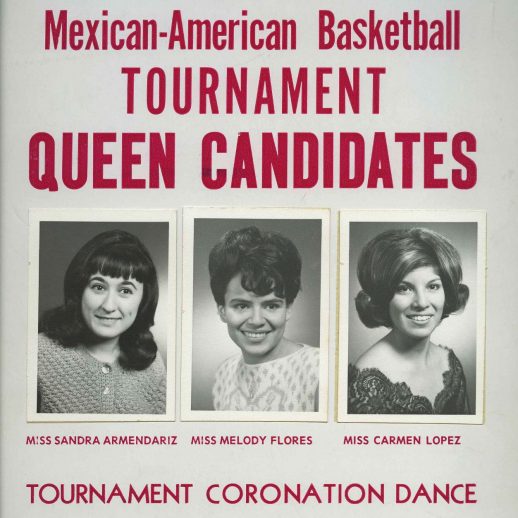

Organizations such as bands and sporting teams maintained social ties. They were also outlets when the larger society did not always welcome Mexican Americans into their midst.

Across from the packing plants along Lawrence Avenue, now Broadway stood a series of restaurants. Among them was El Patio hotel and restaurant with Chata’s next door. When the Guzman family decided to sell Chata’s, the Lopez family took it over and renamed it Connie’s after Concepción Lopez. Lopez got her start making food for parish dinners. Restaurants like these served Mexican American patrons but also helped expose the Anglo community to Mexican food as well.

In the 1950s, Mexican American youth participated in many of the same traditions as the larger community including attending high school and holding beauty contests. Many worked to try to fit in, finding Hispanic cultural traditions embarrassing holdovers from their parents and grandparents.

Latino youth embraced the rock & roll of the era. North High School students Art Martinez and Mike Jimenez were part of the group Doug and the Inn-Truders. Meanwhile, Dolphie Ybarra from Wellington was part of the Fantabulous Jaggs, complete with pompadour!

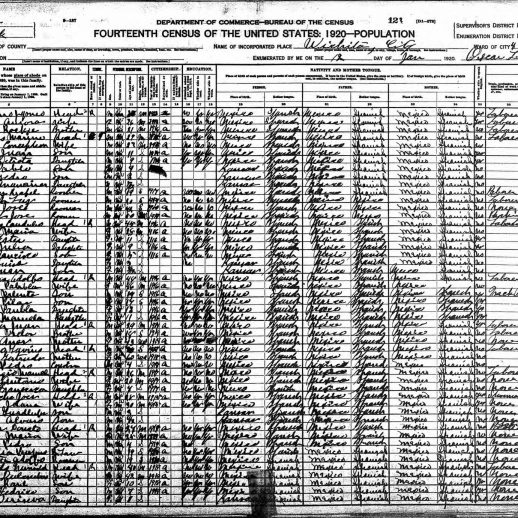

By the time of the 1920 census, clusters of Mexican American neighborhoods had developed. These families lived along Mosley in the vicinity of barrios such as El Huarache and El Rock Island.

In Wichita, elementary schools were segregated although intermediate level classes, like this one from Central Intermediate School, and high school classes could be mixed. Unlike African Americans, or Latinos in places like Kansas City, Latinos in Wichita were not restricted to segregated schools. However, these children did face the pressure to fit in and not speak Spanish.

The athletic facilities of Our Lady also supported local sports teams, such as this basketball team from Cudahy.